Tamez Stronghold

Share

Indigenous response to the U. S. Border Wall

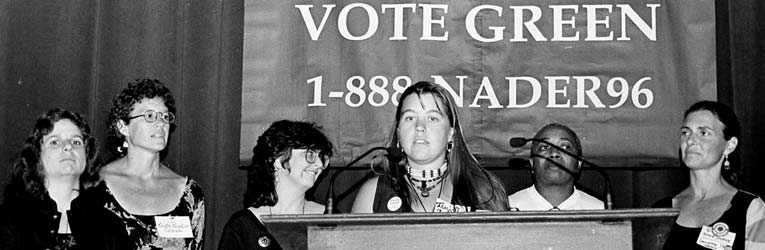

by Wendy Kenin, California Green Party

While many in the Green Party focus on border walls as overseas injustices, the Arizona Greens and other southwestern states GP members have taken a stand against the U.S. border wall now spanning California, Arizona, New Mexico, and Texas. In addition to the wallís assault on the environment, immigrant rights, and democratic processes, the most overlooked concern is its impact on indigenous peoples within U.S. borders.

The U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) under the leadership of Secretary Janet Napolitano has continued construction, “to secure our borders and reduce illegal immigration,” the DHS website states. †Yet continued seizure of land, obstruction of ceremonial pathways, and militarization of the region are devastating native nations located along the international boundary zone from California through Texas.

Arizona Green Party co-chairs Claudia Ellquist and Angel Torres submitted additional language for the Green Party Platform in the section on Immigration in 2007.

“We demand an immediate end to policies designed to force undocumented border crossers into areas where environmental conditions mean dramatically increased risk of permanent injury or death, and mean greater degradation of fragile environments, and the cutting off of corridors needed by wildlife for migration within their habitat. For these reasons we specifically oppose the walling off of both traditional urban crossing areas and of wilderness areas,” the submission recommends.

“We demand recognition of sovereignty in determining independent status of their members by indigenous nations whose people would otherwise be separated by the border demarcations of more recent nations.” The border has obstructed indigenous familial and societal relationships for generations, a problem that the wall has exacerbated.

Relative to egregious Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) raids and citizenship initiatives, the border wall has remained a low visibility issue in national debates on immigration reform. While no-wall activism, border-crossing, environmental issues and local economies take center stage, concerns of indigenous people are marginalized.

Lipan Apache Eloisa Garcia Tamez, program director for†University of Texas†at Brownsville and long-time nurse veteran, stands next to the border wall.

Lipan Apache woman Eloisa Tamez of El Calaboz, Texas has ongoing litigation that has successfully argued indigenous claims to her three-acre property. Repre≠sented by Attorney Peter Schey, Tamez has led the legal fight among local communities impacted by the physical wall. Her case was followed by the Texas Border Coalitionís lawsuit, a cooperative effort by border mayors and business leaders against the wall, with significantly different priorities from Tamezís. In October í08, Tamez received the Henry B. Gonzalez Civil Rights Award from the Texas Civil Rights Project for her tireless efforts to fight the wall.

Grassroots mobilization around Tam≠ezís case has included press releases and national telephone press conferences by which members of various Native Ameri≠can communities have articulated their historical experiences with border region militarism and current impacts of the wall. Representatives on the calls have included Tohono Oíodam, Yaqui, and Chiricahua Apache tribes in Arizona, and Jumano Apache, Chiricahua Apache, and Lipan Apache in Texas. Stories have ranged from spiritual land ties to border agents murdering local native youths in Arizona and Texas.

Margo Tamez, activist, poet, and scholar testified in Oct. 2008 at the Organization of American Statesí Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (IACHR-OAS).

Margo Tamez, scholar and daughter of Eloisa Tamez, testified in October í08 at the Organization of American Statesí 133rd Period of Sessions of the Inter-Amer≠ican Commission on Human Rights (IACHR-OAS). “This wall is being built in the middle of our traditional lands, on the subsistence farmlands of our people who are living todayÖ These are all places that are managed by families, and family is the most primary unit of Apache people. We begin there from the motherÖ Our sac≠red sites are on the other side of that riverÖ”

Tamez continues, “The border wall will disproportionately impact indigenous and poor camposino families on the Texas-Mexico border. Our family will lose title to a portion of our traditional lands and we will be unable to access the property that belongs to us on the other side of this grand wall. Our lands will be divided by the wall. This wall will also displace our people. These are the only lands we have leftÖ so we consider this forced relocation of our people.”

ìOur lands will be divided by the wall. This wall will also displace our people. These are the only lands we have leftÖ so we consider this forced relocation of our people.î

ó Margo Tamez

San Diego Green Rocky Neptun who resides part-time in Tijuana reports on the impact of global politics on communities of northern Mexico. His November 2007 article “A World Without Borders” published on www.mediaLeft.net chronicles the five-day international encampment and border wall protest. He writes: “Here, where the great Sonora Desert begins, Calexico-Mexicali is a city sliced in half, like a piece of toast. Ö The days and nights camped in the blood sand, abutting the great steel wall, surrounded by armed agents, puts the border in context for these young people as both a physical and virtual barrier that kills, segregates, pollutes and is a strategic point of control for wealth and power. It is a barren wasteland, a place of evil, where rights are denied to both people and the Earth.”

In his April í09 article “The Fumes of Empire,” Neptun describes the struggle of the displaced indigenous of Mexico. “Here in Tijuana, Marta would see them night after night; shadows of once proud people; without work, without hope. The men, once great farmers and hunters; wounded by their loss, ashamed, impotent providers and fathers would work a few hours cleaning over-flowing toilets, cleaning spit-soaked walkwaysÖ Here on the border, where the 19th Century meets the 21st, where peasants are ground into urban dust, migration has always been primarily male and only the toughest survived. Yet today, women and children face the structural violence of market capitalism without familial support or the structures of rural social supports.”

The City of Berkeley, California passed a resolution “Condemning the construction of a border wall along the international boundary zone connecting the United States of Mexico and the United States of America” in February 2008. Crafted by Day Labor Center Director Gabriel Hernandez of Hayward, California, the resolution emphasizes Nat≠ive American concerns among other problems with the wall. Green icon Dona Spring, who served for 16 years on the Berkeley City Council before her passing last July, voted in favor of the no-wall resolution.

Other activities going on regarding sacred sites in the border region include a protest by the Oíodam of Arizona at the Mexican Consulate in San Francisco as well as a sacred run in Phoenix to challenge Mexicoís dumping on a sac≠red site on the south side, and against the border wall. Addi≠tionally, the San Carlos Apache put out a press release in May stating that a coalition of organizations are opposing an Arizona Senate act that sets into law plans for a foreign corporation to mine a sacred Apache site in Arizona. Though neither of these targets the builders of the wall, they are relevant to understanding the situation among Native American communities whose traditional land use areas lay in the border region.

Native American activists have also taken the issue of the wall to international forums. Chiricahua Apache Michael Paul Hill of San Carlos, Arizona spoke at the †Seventh Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues in April 2008. “Over 1400 miles of the U.S.-Mexico border is the traditional territory of the Apache people. The Apache people must be given the opportunity to participate in the environmental, economic, social, and political decision-making in the region,” Hill stated.

In a public statement, the IACHR-OAS concluded that it had, “received troubling information about the impact that the construction of a wall in Texas, along the U.S.-Mexico border, has on the human rights of area residents, in particular its discriminatory effects. The information received indicates that its construction would disproportionally affect people who are poor, with a low level of education, and generally of Mexican descent, as well as indigenous communities on both sides of the border.”

In March, University of Texas Clinical Law Professor Denise Gilman, who spearheaded the Texas border wall hearing at the OAS and heads the University of Texas Work≠ing Group on Human Rights and the Border Wall, joined forces with Ralph Naderís non-profit group Public Citizen to file a lawsuit against federal agencies for withholding documents about planning and placement of the border wall.

DHS completed construction of the wall at Tamez Stronghold in El Calaboz, Texas on April 23, against court orders to further consult with the family before commencement. The case is scheduled for a jury trial in October 2009. Eloisa Tamez has started a letter-writing campaign to the White House, especially to Michelle Obama. Tamez Stronghold remains a focal point for pilgrimage, inspiration, and mobilization on the endurance of justice and self-determination in our day.

Wendy Kenin recently joined the Green Pages Committee and has been a Green active in the rights of indigenous peoples for decades. She has served on the Berkeley Peace and Justice Commission since December 2007, and was elected vice chair in 2009.

Aniceto Garcia, father of Eloisa Garcia Tamez, farmed the land that is now divided by the wall. He stands between Jesusita Garcia to his right and Innocente de los Santos to his left in this 1949 photograph.