California Greening Is Becoming a Reality

Share

Twelve victories in 1998, Thirty California Greens are now in office

With its first Governor/Lt. Governor ticket ever, together with a record number of victories on the local level, the Green Party of California had a banner year in 1998.

Former US Congressman Dan Hamburg was California’s first Green gubernatorial candidate. His running mate was California Environmental Protection Agency scientist Sara Amir. Both finished first among the five ‘third’ party candidates in their races. Amir’s 3% of the vote was also the highest for any third party Lt. Governor candidate in California since 1938.

Hamburg, as the highest ranking former public official to run with a California third party in almost 30 years, attracted significant media attention, eclipsing what Green candidates had received four years ago during the last statewide elections. Every major newspaper in the state covered the race, focusing on the ‘threat’ Hamburg presented to the election chances of Democratic candidate Gray Davis.

At a forum sponsored by the Southwest Voter Education Registration Project in Los Angeles – the only forum in which Hamburg was able to appear side-by-side with Davis and Republican Dan Lungren – Hamburg stole the show. With an electrifying speech before 1,000 Latino organizers and elected officials, he brought the crowd to its feet for three standing ovations.

Hamburg was the only to speak for bi-lingual education for all Californians. He was the only one of the three to speak against the death penalty. Citing California’s 25% child poverty rate, Hamburg argued for living wages and the decentralization of economic power and control. He criticized the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), which both Davis and Lundgren praised, calling called attention to the massive US job loses suffered because of it. Then he spoke of the struggles of the Zapatistas in Chiapas, where NAFTA undermines local economic self-reliance. The crowd rose to its feet in thunderous applause, seemingly in disbelief that they were hearing these kind of issues discussed in a major political forum.

One of the goals of the Green statewide campaign was to convince California’s progressive movement that the Green Party should be its electoral voice. by Most of the key progressive weekly newspapers in the state endorsed Hamburg’s campaign in the June open primary, including the LA Weekly, San Francisco Bay Guardian and the Sonoma County Independent. In the November general election however, these publications backed away from endorsing him because of their fear of ‘electing the Republican’. They were willing however, to make a pro-Green statement in the Lt. Governors race – Amir, a native of Tehran who had fought for womens’ rights in Khomeini’s Iran, was endorsed by the LA Weekly, San Francisco Bay Guardian and the Sacramento News and Review (as well as the 2,500 member California Association of Professional Scientists).

In other partisan races, Greens finished first among California’s six minor parties for the State Board of Equalization, and first in for out of six Congressional races. As of October, 1998, Green registration increased to 98,443, the highest its been since early 1992.

It was in the municipal elections however, that the Greens had the most success. Founded in 1990, the Green Party of California has successfully focused targeting local races where its candidates can effectively communicate a grassroots message. Progress has been slow but steady and the challenge remains daunting. But after eight years, the news is good: election after election, things just keep getting better.

A record 41 California Greens ran for office in 1998, including a record 30 for municipal and county office in 1998. A record twelve were victorious, including a record nine for city council. This continues an impressive trend, with an increasing number of Greens winning city council seats with each electoral cycle – 1990 (1), 1992 (2), 1994 (4), 1996 (6), and 1998 (9).

Success occurred in new and old places in 1998. For the first time, city council victories occurred in Morro Bay (Colby Crotzer), Nevada City (Kerry Arnett), Santa Cruz (Tim Fitzmaurice), and Sebastopol (Larry Robinson). In Santa Monica, a second seat (Kevin McKeown) was added, while in Point Arena, a second seat was retained with a new candidate (Debra Keipp).

All three city council incumbents also fared well. Stephen Schmidt (Menlo Park), Alan Drusys (Yucaipa) and four-time winner Dona Spring (Berkeley) were all re-elected, each finishing first (Schmidt’s and Drusys’ races were multi-seat). With these victories, a record 16 Greens now hold city council seats statewide. In three cities – Arcata, Point Arena and Santa Monica, there are two Greens each on the city council.

Unifying Green candidates is their focus on sustainable development, responding to the tremendous growth pressures throughout California. The response to this agenda from voters suggests a growing base of Green support statewide.

This success has not gone unnoticed by Green opponents. For the first time, aggressive, well-funded direct-mail hit pieces were targeted against Green candidates, particularly Drusys and McKeown. Both managed to win their seats in spite of these attacks.

Other Green candidates also ran strong city council campaigns. Although they did not win, these candidates offer additional hope for the party’s future – Brad Freeman, Arcata; Budd Dickinson & Chris Kavanagh, Berkeley; Nancy Lynn Abrams, Eureka; Bonnie Bennett Grass Valley, Rainy Cloud Greensfelder, Nevada City; and Bill Patterson, Windsor.

In races for other offices, Selma Spector won a spot on the Rent Stabilization Board in Berkeley, finishing fourth out of ten contenders for five seats. William Bretz won two seats, one on the Resource Conservation District of Greater San Diego County and the other on the Crest/Dehesa/Harrison Canyon/Granite Hills Planning Group.

In San Francisco, Greens waged their first serious campaign for a local seat. In the San Francisco Board of Education race, Pamela Coxson made a very impressive showing. She finished sixth out of 12 candidates running for three seats, in what was a single, city-wide at-large election.

In total, a record 30 California Greens currently hold local office of some kind, including city councils, school boards, water boards, rent control boards and others.

Colby Crotzer, City Council Morro Bay WIN

For many years, development in Morro Bay has been limited by the city’s short water supply. But in recent years, the city has purchased additional supplies from the state of California, selling it at discounted rates to spur new development.

Concerned about runaway construction and unplanned growth, Coltzer ran against what he termed the ‘pro-development/anti-environment’ monopoly on the city council. Despite being heavily outspent on newspaper advertising and direct mail pieces — paid for by the development and real estate interests backing his opponents — Crotzer ran a successful grassroots campaign. He finished second out of four candidates for two open seats, winning by a 12-vote margin, out of the 4,492 votes cast.

His campaign style was simple and direct. He sought input from voters wherever he could – at supermarkets and street corners. He also walked in every one of the city’s precincts for 2 1/2 months before the election, hitting the streets even before absentee ballots were in the mail.

Crotzer advocated revising the city’s general plan and mapping out future growth, rather than simply reacting to individual development proposals. He also stood for a more approachable city council and a more accessible city government. Crotzer was endorsed by Advocates for a Better Community, a 20-year-old environmental group that mailed a newsletter to voters, endorsing Crotzer and emphasizing the excessive growth records of his opponents.

After only a short time in office, Crotzer has shifted the parameters of city council debate, raising hope that environmental candidates will win two more seats in 2000 and gain the majority. This would represent a fundamental shift in local politics. Historically, members of environmental groups have been reluctant to even take sides in city elections, wary of alienating the well-funded and well-connected pro-development forces, whose help is often needed to realize local environmental projects.

Alan Drusys, City Council, Yucaipa WIN

Development was also a critical issue in Yucaipa, a rural San Bernadino County foothill community, where residents are dealing with the negative impacts of development sprawling from the neighboring Riverside-San Bernadino-Redlands metro area.

Running on a slow-growth platform, Alan Drusys was re-elected to his second four-year term, finishing first among five candidates for two seats. He accomplished this despite an aggressive direct-mail campaign against him. The attack mailing was designed to appear as if it was produced and paid for by the state Green Party. It even included the state party’s official Sacramento address and web-site.

Playing upon the perceived conservative social leanings of the Yucaipan electorate (approximately 11,000 Republicans, 8,000 Democrats), the mailer claimed the Green Party was to the left of the Marxist-Leninists, and focused on the party’s supportive stances of pro-choice and gay/lesbian and rights.

How much did the mailer hurt? Drusys felt it cost him as much as 1,000 votes. But he still finished first with 4,775 votes, to 4,541 for the 2nd place finisher and 4,496 for the 3rd.

Drusys felt he withstood the direct-mail attack for two main reasons – his record in office, and his accessible, grassroots campaign style. For five weeks, Drusys stood in front of grocery stores, talking to residents, emphasizing the difference between himself and pro-growth candidates. He did the same thing, together with supporters, walking door-to-door in the city’s neighborhoods. Development as an issue had recently reached a fever pitch locally, when 700 acres of citrus groves were cut down to build 2,200 new homes.

Drusys focused on preserving existing affordable housing, in particular protecting the local mobile home park rent control ordinance from being weakened. Other issues were traffic, loss of quality of life, and better treatment for city employees.

Drusys combined his fundraising together with the other environmental candidate in the race (a current planning commissioner who eventually finished fourth). The two raised and spent $7,000 combined, mostly from small donations under $100.

Drusys’ two main opponents were Republicans. Both were also former police officers. Supported by local conservative state Assemblyman Brett Granlund, they ran on a pro-growth platform, emphasizing less government and lower taxes. Neither appeared at the two candidate forums.

Even though Drusys was re-elected, little is expected to change on the council, as the Republican that won the other seat is replacing ironically another, conservative, outgoing Republican, former police officer on the Council. As such, the 3-2 ‘pro-growth, sales-tax-generation-at-all-cost’ city council majority remains.

Kevin McKeown, City Council, Santa Monica WIN

A densely populated beach community of eight square miles, Santa Monica lies at the base of the Santa Monica Mountains along the Pacific Ocean. It is surrounded on three sides by the city of Los Angeles. Real estate in Santa Monica is expensive and prices are only going higher. The defining community issues include housing, traffic and development.

Kevin McKeown, a 22-year Santa Monica resident, swept into office advocating tenants and workers rights, affordable housing and sustainable development. He campaigned for more parks and crosswalks, better education, and preservation of neighborhoods.

Although he was a first-time candidate, McKeown had a long history of prior public involvement. For years he’d arrive at City hall wearing one activist hat or another: neighborhood organizer, affordable housing supporter, education advocate, and technology consultant. McKeown also contributed columns regularly to community’s several weekly newspapers, giving residents ample opportunity to learn about his ideas.

Backing McKeown was a broad coalition of progressive forces, led by Santa Monicans for Renters’ Rights (SMRR). SMRR helped establish rent control in Santa Monica in the late 70’s, and since then has built an impressive grassroots campaign organization, championing progressive issues along the way. Renters comprise more than 65% of Santa Monica residents, and SMRR spends upwards of $100,000 each election to support its endorsed slate of City Councilmembers (as well as its School Board, Rent Control Board and College Board candidates).

Union support also played a significant role in McKeown’s success. He earned the endorsement of the Hotel Employees and Restaurant Employees (HERE) Local 814 and Santa Monicans Allied for Responsible Tourism (SMART). Both groups work to improve the condition of low wage workers in Santa Monica’s vibrant luxury tourist/visitor economy, confronting issues such as union-busting and living wages.

In 1996, this same tenant/labor/Green coalition, also featuring key neighborhood and feminist activists, came together to elect Green Michael Feinstein. Now in 1998, the coalition blossomed into a smooth-running operation of phone banking, precinct walking and getting-out-the-vote efforts.

McKeown also built connections to new groups. He shocked Santa Monica’s old-guard political establishment when the police and firefighters’ unions endorsed his candidacy over one of the conservatives, and contributed significantly financially to his campaign. McKeown also received support in affluent parts of town, which traditionally had not responded to progressive ‘renter’ candidates, as a result of the city’s historical division over rent control. However, McKeown transcended that wedge issue even before he was elected by helping create the first-ever neighborhood group in the northern part of the city. He also gained support among homeowners there just a few months before the election, when he fought a proposal before the city council that, if passed, would have made it easier for property owners to demolish tasteful old Craftsman homes and build so-called ‘monster mansions’ in their place.

McKeown also received endorsements from the Sierra Club, the (5,000-member strong) Santa Monica Dog Owners’ Group and the Southern California chapter of Americans for Democratic Action.

As the campaign wore on, McKeown needed every bit of this support, as he was pummeled by merciless, last-minute direct-mail attack pieces. Three different mailers misrepresented Green policies, attempting to paint McKeown as unfriendly to both renters and homeowners, and a candidate willing to drive out a local hospital at the expense of health-care for seniors. This fear-mongering was described by L.A. Times Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and Santa Monica resident Robert Scheer as ‘green-baiting’. The Nation magazine called it ‘red-baiting’.

Still other flyers accused McKeown of concocting a ‘secret plan’ to fire Santa Monica’s police chief, which McKeown denied as ‘blatantly untrue’. This charge surfaced during an atmosphere of public concern over several uncharacteristic gang-related shootings. “City Council candidate Kevin McKeown is a Green Party member who will do anything to get elected… even compromise our public safety” the flyer read. McKeown viewed these flyers as payback from local conservatives incensed that he had received the police and fire unions’ endorsements.

McKeown shone during the several televised debates on local cable (including two sponsored by the League of Women Voters), and he seized the moment during the free five-minute segment offered to each candidate, to state their views on the city’s own cable station CityTV. (This free tv time per candidate was a new reform that had been promoted in the prior city council campaign by Feinstein).

McKeown and supporters knocked on doors of thousands of residents. His bright green and black signs dotted lawns and decorated windows throughout the city. However, many sign were repeatedly torn down and stolen. One was burned in a resident’s front yard. These tactics backfired on McKeown’s opponents, however, when local newspapers wrote stories and McKeown’s public profile soared.

Campaign excitement also increased eight days before the election, when Ralph Nader came to Santa Monica and endorsed McKeown during a press conference in front of city hall. A photo of the two ran in one of the local papers.

Santa Monica is already the largest US city in which a Green has been elected. The significance of McKeown’s election was not only that it seated a second Green on the city council, but that it gave Santa Monica its first progressive council in many years. For updates, check out McKeown’s impressive interactive candidate/officeholder website at www.mckeown.net.

Larry Robinson, City Council, Sebastopol WIN

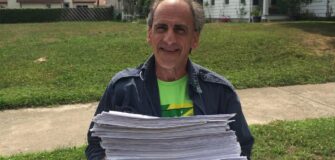

Another first-time candidate, Larry Robinson not only won his race, but he finished first among six candidates for three seats. His campaign was remarkably similar to those of other successful Green candidates.

In Sebastopol during the campaign, growth and traffic were on the minds of most residents. Robinson talked about sustainability and civility. He questioned whether Sebastopol should continue to be a bedroom community (linked to nearby Santa Rosa), or whether it should evolve into a sustainable community unto itself. To be sustainable Robinson argued, Sebastopol must add affordable housing, local jobs and local shopping. Such new development shouldn’t come as sprawl, however – in 1996, Robinson led a local initiative effort to establish a 20-year urban growth boundary. The initiative passed 72% to 28%.

Robinson communicated his message via a vigorous door-to-door campaign. Sebastopol has a population of 7,800 (2,500 households), so Robinson was able to knock on every door personally between July and October. In October, together with a group 25 supporters, he covered the city a second time. Supporters also put up 100 18″ x 24″ lawn signs in yards across the city.

Robinson raised about $4800, mostly in small $20 to $100 contributions, coming from 90 or so residents. Another $1200 came through an evening fund-raiser of poetry and music. This enabled Robinson to send out a direct mail piece to every registered voter. He also spoke to several civic groups and participated in three candidate forums. Robinson received endorsements from the Sierra Club, Sonoma County Conservation Action, the Rural Alliance and the Sebastopol Police Officers Association.

In spite of his personal mandate from the voters, Robinson often finds himself in the minority on development issues, opposed by councilmembers who consider themselves liberal Democrats and environmentalists, yet who consistently vote for unsustainable development policies and projects.

Tim Fitzmaurice, City Council, Santa Cruz WIN

In 1998, Santa Cruz faced a watershed election. Either the next city council would continue Santa Cruz’s pattern of growth into a bedroom community for San Jose, or it would change the direction of local government.

Tim Fitzmaurice’s platform emphasized Santa Cruz as a locally self-reliant community, based upon responsible goals, environmental integrity and a standard of living supportive of local working people. These issues came into focus right before the election, in the context of the community response to a specific plan for rebuilding the city’s beach area.

The Beach/South of Laurel Plan proposed moving a street to expand the local amusement park. This would require removal of housing occupied by poorer residents. It would open the door to gentrification, and to large businesses competing with downtown. And, it would significantly increase traffic into the cul de sac of the beach area. These issues, and the failure of the city council to include the public in the planning process, led to a general call for change – in the plan and within the city council itself.

A Green since the party’s founding days, and a union member for even longer, Fitzmaurice brought experience as a member of the Santa Cruz Transportation Commission, a lecturer at the University of California, and a critic of the Beach Area Plan (to expand the boardwalk and gentrify the beach area). He ran as part of an informal, three-person slate, standing for fair wages, affordable housing, smart growth, and open planning processes. They were supported by the local progressive organization – the Santa Cruz Action Network, the local Service Employees Union, most Democrats, and the Greens. This coalition was able to distribute the “doorhanger,” the sine qua non of Santa Cruz elections. Fitzmaurice finished second out of eight candidates for three seats.

Even though it didn’t prevent him from winning, Fitzmaurice’s Green affiliation caused painful divisions in Santa Cruz overwhelmingly Democratic local politics (85% of registered voters are Democrats). Ironically, it was Democrats who originally sought out Fitzmaurice to run. Later they learned of his Green registration. Subsequently, many asked him to register Democrat. Fitzmaurice was also publicly barred from speaking at a number of Democrat club candidate forums.

However at other clubs, Fitzmaurice was supported, including by club officers, in spite of his Green affiliation. This was because his politics were more in alignment with those of the club than were those of the pro-growth Democrats. Fitzmaurice was also supported by Democratic Assemblymember Fred Keeley, who had worked together with Fitzmaurice on Santa Cruz transit issues for ten years.

Fitzmaurice’s response? “I chose the Green Party because of the potential unity of labor and environmental concerns. It is an issue-based party, not a label-based party. That’s why I am best described as a Green.”

In the future, there may be a move by some Santa Cruz Democrats to make it more difficult for other Greens to receive the same progressive endorsements Fitzmaurice did, because the ‘disruptive’ nature of Fitzmaurice’s candidacy. At the same time, it may be hard to deny the Greens.

“My campaign spoke about traffic concerns, water problems, and unmanaged growth. These issues resonated in Santa Cruz”, said Fitzmaurice after the election. “They seemed to express a deep concern about where the local community was headed. Even though the former council was certainly liberal, people wanted something different. The Green virtues seemed to be an unambiguous expression of this difference. I heard it often on the campaign trail: ‘Are you Democrat?’ ‘No, I’m a Green.’ ‘That’s better than being a Democrat.’