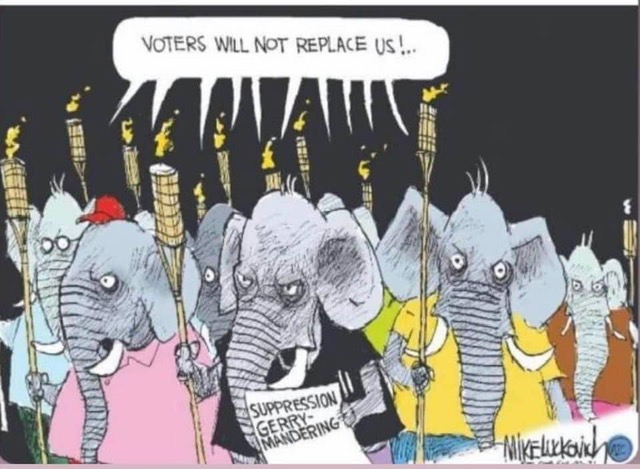

Eliminate Gerrymandering with Proportional Representation

Share

Gerrymandering is one of the anti-democratic features of the exclusionary single-member-district, winner-take-all plurality elections that are predominant in the United States.

Proportional representation would not only create an inclusive democracy in which all political viewpoints get their proportional share of representation in legislative bodies, it would also render gerrymandering impossible.

Gerrymandering is when politicians draw election district lines for partisan advantage. It gives the party with the power to draw the lines more representation than their votes would justify if representation were proportional to the vote each party receives. Incumbents gerrymander district lines to include more of their supporters and make their re-election a foregone conclusion. With gerrymandering, the politicians pick their voters, instead of the voters picking their politicians.

For example in Wisconsin, as a result of partisan gerrymandering by Republicans after the 2010 census, in 2018 Democrats won 54% of the statewide popular vote in assembly races but only 36% of the seats. The 46% minority vote for Republicans won them 64% of the seats thanks to gerrymandering.

Because Republican voters are overwhelmingly white, partisan gerrymandering also yields racial gerrymandering. Racial gerrymandering is illegal under the 15th Amendment, but U.S. Supreme Court decisions since 2013 have made the legal remedies against racial gerrymandering enacted under the Voting Rights Act of 1965 impossible to enforce.

In 2013, in Shelby County v. Holder, the Supreme Court gutted the pre-clearance provision in Section 5 of the Voting Rights Act that had required pre-approval by the Department of Justice of changes in voting procedures in jurisdictions with a history of voting discrimination. Section 4, which defined those jurisdictions, was ruled unconstitutional. Within hours of the Shelby decision, states previously covered by the pre-clearance provision started enacting laws – some of which had previously failed to pass pre-clearance – that are designed to suppress the vote of racial minorities, such as photo ID requirements and voter roll purges.

In 2019, in Rucho v. Common Cause, the Supreme Court ruled that partisan gerrymandering was constitutional. In 2021, Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, the Supremes ruled that in order to strike down a voting procedure on the grounds of racial discrimination, a plaintiff had to prove racist intent, not only effect, rendering relief under Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act for racial discrimination far more difficult.

To get around the 15th Amendment, Jim Crow voting discrimination was always couched in race-neutral language through such measures as poll taxes and literacy tests, which had the effect of disenfranchising most of the poorer half of whites as well as almost all African Americans in the South. The Voting Rights Act was supposed to remedy that voter suppression, but it is back in full force. In the Supreme Court hearing on the Brnovich case, the lawyer for Arizona Republicans defended a racially discriminatory voting procedure by saying that eliminating it “puts us at a competitive disadvantage relative to Democrats.”

Democrats have been nervously complaining that Republicans, who control both legislative chambers and the governorship in 30 states, are busy gerrymandering state legislative and House districts in the states they control to their own partisan benefit. But Democrats are gleefully doing the same in states they control like Illinois, Maryland, New York, and Oregon. When the dust clears on gerrymandering this year, the partisan impact may be “slightly less biased in the GOP’s favor than the last decade’s” when Republicans maxed out partisan bias in redistricting after the 2010 census.

Which major party may be winning the partisan gerrymandering battle does little to change the disenfranchisement of Greens and the over 40% of voters who are not affiliated with either major party. We are excluded from electing our own representatives by the single-member-district, winner-take-all voting system. Under this system, most districts are non-competitive one-party districts. Members of the major party that is the minority in a single-member district are also excluded from electing people who represent their political viewpoint.

Partisan gerrymandering only makes the problem of non-competitive elections worse. Over 90% of House districts and over 95% of state legislative districts are non-competitive one-party districts. As a result, tens of millions of us are perpetually represented by politicians we oppose with no hope of changing our representation by voting.

Independent redistricting commissions are often proposed to remedy partisan bias in redistricting and non-competitive districts. In most states where these commissions exist, their independence has been “undermined by partisans” this year. The results of independent redistricting commissions after the 2010 census yielded mostly non-competitive one-party districts and bias toward one of the two major parties. For example, in 2011, an independent redistricting commission drew new House district lines in California. In 2014, Democratic House candidates won 57% of votes in California’s 53 House races, but 74% of seats. Similarly, in New Jersey in 2011, a bipartisan commission with one public interest independent drew state assembly lines that then resulted in 2013 in Republicans for the state assembly winning 51% of the vote, but only 40% of the seats.

Redistricting can easily game single-member district lines for partisan gain, but not in multi-member districts using proportional ranked-choice voting (RCV). In fact, the only way to end partisan bias and non-competitive one-party districts is to have proportional representation from multi-member districts. RCV in multi-member districts yields proportional representation of all political viewpoints no matter where the district lines are drawn.

The more seats up for election in a multi-member district, the more proportional the results will be. The winning threshold for a 3-seat district is 25% plus one vote. A party or political viewpoint with 20% support would not get representation. If the districts were nine seats each, the winning threshold would be 10% plus one vote. The 20% party would get two of the nine seats. See this write-up and video at Fair Vote for a short, clear explanation of how proportional RCV works.

Greens should be promoting proportional RCV to end partisan and racial gerrymandering at the state and federal levels. If there is not a bill in your state legislature, demand that your representatives introduce one. We do have a bill to support in Congress, the Fair Representation Act (H.R.3863), which would require proportional RCV for House elections and single-seat RCV for Senate elections. The bill only has seven co-sponsors. Most progressive Democratic leaders like Pramila Jayapal and “The Squad” are not among them. No Senator has introduced companion legislation.

Every Green running in a House or Senate race should make this bill a campaign issue and demand that their opponents pledge to support the Fair Representation Act. Make news with their responses. If they respond by supporting it, declare victory. If they refuse to support it, raise hell.