The Citizens Party

Share

A third-party forerunner of the Greens

A third-party forerunner of the Greens

Editorial by Mark Dunlea, Green Party of New York State

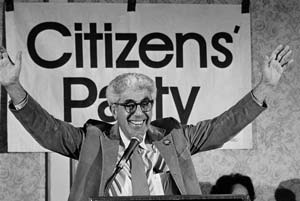

In the early days, it was said that if you asked a group of five Greens what the party was about, you were likely to get half a dozen responses. My own history starts with the Citizens Party (CiP), the environmental party that Barry Commoner helped launch with his 1980 presidential campaign.

In 1982, the Citizens Party was one of the signers of an international federation of ecological parties, which most prominently included the West German Green party, the “superstar” of the movement through winning entrance into the national parliament. Even though this agreement was signed by the best known German Greens, notably Petra Kelly, there are differences of opinion as to whether this was a formal affiliation or a more loose statement of solidarity and principles.

As co-chair of the NYS chapter and a member of the national executive committee, I understood the agreement to be more formal. In 1984, my wife was the campaign manager and I the national organizer for the presidential candidacy of Sonia Johnson, the feminist excommunicated from the Mormon Church over the ERA. In an effort to attract media attention in the U.S., we decided to organize a ten-day tour of European countries where we met with the various Green Parties, who treated our party like a sister organization. Whenever prominent Greens came to the U.S., particularly Washington, D.C., they would ask to meet with the CiP.

Sonia Johnson, founder of Mormons for E-R-A, addresses a news conference lending her support to a planned demonstration in Richmond for passage of E-R-A during the 1980 session of the general assembly. Mrs. Johnson was recently excommunicated from the Mormon church for vocal support of the Equal Rights Amendment. — Image by © Bettmann/CORBIS

In 1984, author/activist Charlene Spretnak announced an “invitation only” first Green Party meeting on the same weekend as the Citizens Party national presidential nomination convention both in the Minneapolis/St. Paul area. Why the CiP was not included was a mystery to us, but we were far more worried about our own fate as there was a dichotomy in agreeing where to focus campaigns.

Some felt that the CiP was too focused on Barry Commoner, and that it should also focus on organizing first at the local level, an argument still debated among Greens. Commoner was perhaps the best-known environmental scientist in the U.S. if not the world when the CiP was launched in 1980. His bestselling book, The Closing Circle, introduced the idea of sustainability to a mass audience. He argued that the American economy had to restructure to conform to the laws of ecology. Wikipedia states that “Commoner postulates that capitalist technologies were chiefly responsible for environmental degradation.” The Citizens Party focused on promoting democratic control of the economy.

The most prominent proponents of the alternate approach of starting in communities were Rev. Lucius Walker, Arthur Kinoy of the Center for Constitutional Rights, and Marilyn Clements (who later launched Healthcare NOW! to promote single payer healthcare).

The CiP’s 1980 Presidential campaign had mixed results. It successfully launched a national progressive ecologically centered party. But it bet heavily on getting five percent of the national vote, which would provide millions of dollars retroactively to finance the campaign and then a similar amount for the next one. However, moderate Republican John Anderson launched an independent candidacy and transferred the five percent to his party, leaving the Citizens Party with only .25 percent (221,000) of the vote. Unfortunately, the Party had bankrolled the campaign through large loans with all party raised funds having to pay off the debt rather than build the party, which further undercut fundraising.

Also leading to the Citizens Party demise in 1984 was low electoral success. Despite the low presidential vote, dozens of state parties were organized, with scores of CiP candidates running for Congress in 1982, more than any other progressive party in generations. When almost all the candidates came in at one or two percent, discouraged members lost energy to keep the party moving forward.

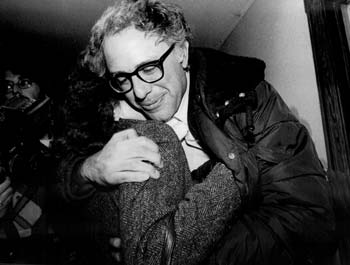

The 1984 Presidential election was the last gasp. Commoner pushed the party to run in only one state—Vermont, where the Citizens Party had won an election in Burlington at the same time Bernie Sanders got elected as mayor. If the CiP could win Vermont by investing all the resources there, and the national election was largely a tie, then the CiP would be the “king maker” in the electoral college. This idea was not well received as party activists felt it would sacrifice growth across the country.

The grassroots activists in the party felt it should play to the party’s strength, which was the women’s movement, so they had successfully recruited Sonia Johnson. Johnson managed to become the first independent candidate to ever qualify for presidential matching funds and won the nomination. But the internal strife, financial debt and low voter results led to the party’s demise.

The last Citizens Party campaign I know of was in NYS near Ithaca in 1985, where Tim Joseph, a state leader, pulled 30 percent of the vote for County Legislature in a partisan election, one of the best showings ever for the party. After the CiP ended, Joseph was recruited by the Democrats, won the election and served as Chairperson of the Tompkins County Legislature.

As a side note was the Citizens Party’s relation to the Alinsky Community Organizing Group (ACORN). Electoral politics was always a strategy used by ACORN to try to win power for its members. In the late ’70s it decided to organize a third party, and launched a campaign to organize 20 states by 1980 to qualify for presidential matching funds. Finding its main community partners, namely African-American churches and the unions, loyal to Democrats, ACORN retreated. Several of its staff left at that point to work with the CiP, including myself and its national organizer, Bert Deleeuw. ACORN later focused on fusion, creating the national New Party and then the Working Families Party in New York.

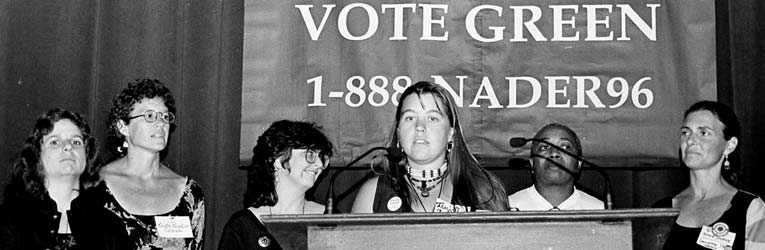

After taking a few years to recover from the CiP, I worked to put together a Green Party in the Capital District of NY and then statewide. I encouraged the Greens to run a presidential campaign in 1988, building on Johnson’s success in qualifying for federal matching funds. Once the qualifying threshold was crossed, obtaining matching funds greatly changed the cost effectiveness of fundraising, especially direct mail, making it much easier to expand the party’s base and do outreach. I met Howie Hawkins, living in White River Junction in Vermont. He dismissed my suggestion as premature, arguing the greens should run only local candidates, not for state or national office.

In the early years of the Green Party, various movements came and went, including ecofeminism, deep ecology, municipal anarchism/left greens, and animal liberation. One of the strongest was the bio-regional movement, which focused on organizing the party based on natural ecosystems, rather than on artificial political boundaries.

I initially organized a capital district chapter of the Green Party in the late 80s, with a somewhat strained relationship with a green bio-regional group in the area that seemed to have already peaked. We focused more on issue organizing and education rather than electoral politics.

Over the next five years I ran for a variety of local offices as a Green, trying to build the party. Several of the initial races utilized the strategy of fusion. New York is one of the few states that allow you to run on more than one party line at the time, combining your vote results. I managed to win a partisan race on the Green line with a cross-nomination for town board. I also pulled more than 20,000 votes in a high profile race for State Assembly by also winning the Democratic primary against the party machine. My conclusion was that the higher vote total for me as an individual did not translate into building the Green Party, and abandoned fusion as a strategy.

In my first race, I had decided to run in order to create a Green Party through an election. That didn’t work. People focused too much on me and not the party, with the needs of the campaign overshadowing party-building work.

In 1991, I helped pull together the Green Party at the state level in order to start running elections. There were already several other green organizations in the state, the largest being the Buffalo Greens. In order to qualify as an official political party in NYS, a party’s gubernatorial candidate had to win at least 50,000 votes. Because of our focus on electoral politics, New York ended up being one of the first Green Parties to organize on state lines.

The Green Party has seemed to move past the ideological debates that dominated the first dozen years of the party. But at the national level at least, there seems to be less of a commitment to the initial concept of the Greens as an anti-party. The unwillingness of the national party to embrace a movement organizing strategy seems to limit its electoral growth.