Taking the lead in green trends

Share

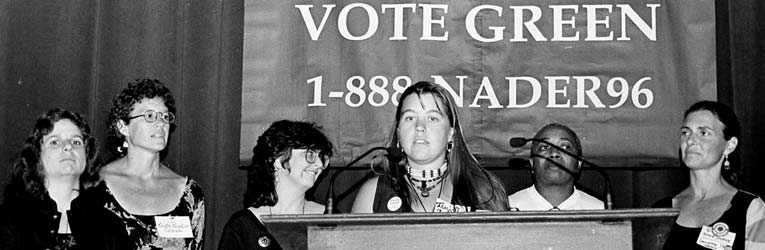

A look a four who live following the Green Party platform

by Wendy Kenin, Green Party of California

As a grassroots political party, Green members tend to see their party more as a movement than a political affiliation. As a result many Greens have made being Green a lifestyle rather than just a box they check on their voter registration card. As many people around the world are just starting to follow a green trend, party members long ago built these values into their lives. Green Pages examines four Greens who are leaders in the green movement.

ìDecentralization of the Green Party values speaks to me. I believe that revolution is neither singular nor static. I live my life so that every day, every breath, is an opportunity to affect viable political change.î Yasmin Kenny

Yasmin Kenny – Youth Activism

It was in 2005 that Yasmin Kenny of Tampa, Florida returned to Germany to visit relatives and found that in her five-year absence they had taken to composting due to policy from new German Green Party elected leadership. ìI saw all these changes in Germany, and I knew it was because of the Green Party.î So she came home to the U.S. and registered Green.

It was in 2005 that Yasmin Kenny of Tampa, Florida returned to Germany to visit relatives and found that in her five-year absence they had taken to composting due to policy from new German Green Party elected leadership. ìI saw all these changes in Germany, and I knew it was because of the Green Party.î So she came home to the U.S. and registered Green.

ìDecentralization of the Green Party values speaks to me. I believe that revolution is neither singular nor static. I live my life so that every day, every breath, is an opportunity to affect viable political change,î Kenny said.

Kenny has been involved with the Southern Energy Network since 2005, assembling the southern statesí environmental crises into a cohesive story. She became a Florida representative to the National Council of the Student Environmental Action Coalition (SEAC) in June ë09, joining the ranks of a devoted frontlines national volunteer youth organization. SEAC builds coalitions and campaigns on issues such as green jobs, mountain justice and mountaintop removal, climate change, voting, fair food, labor, militarism and the environment.

ìGrassroots democracy is the way to go,î Kenny proclaims. ìThe focus on social justice as not separate from environmental justice is really important to me. You cannot have one without the other.î

Remarking on oil, coal, and uranium, Kenny works to raise awareness on the United Statesí irresponsible energy practices, emphasizing, ìThe mainstream rhetoric almost never includes the communities and lands that are devastated by these things.î

ìVoting is the least democratic thing I do,î explains Kenny. ìPolitical participation is often conceptualized in the U.S. as a once-every-four-years event; a struggle worth persevering for, will not be granted by a magic ballot booth.î

ìA lot of my artwork evolves around Green ideas and philosophy. I integrated the Green philosophy into my studio-based work and into my community-based work.î Michael B. Schwartz

Michael B. Schwartz – Green Arts Jobs

Arizona-based community mural artist Michael B. Schwartz became Green in the 1980s in Philadelphia as he was protesting U.S. military involvement in Central America and beginning his art career.

Arizona-based community mural artist Michael B. Schwartz became Green in the 1980s in Philadelphia as he was protesting U.S. military involvement in Central America and beginning his art career.

Schwartz found inspiration in the work of German Green Party politician and artist Joseph Beuys, who pioneered participatory arts in the twentieth century. ìIn the broadest sense, using the metaphor of Green, we were midwives of social change,î said Schwartz. This approach sought to holistically heal and mend, to be self-sustainable and regenerative, he said.

ìI saw it as a cultural movement. The political part wasnít flushed out. The way to peopleís hearts and minds, the way to really demonstrate what we meant, was to give people a picture of what we were talking about.î Schwartz uses his art medium to promote sustainability inclusive of social, cultural, and political issues.

ìA lot of my artwork evolves around Green ideas and philosophy,î he explains. ìI integrated the Green philosophy into my studio based work and into my community based work.î Schwartz uses recycled materials, and calculates the carbon footprint of his projects.

ìIf youíre just digging in your garden, thatís great, youíre making a garden. If youíre digging with a few friends, thatís even better,î Schwartz said. ìWhatís even better is when the things that you grow are a product that you bring to a local market. Thatís when it becomes regenerative.î

Translated into todayís terms, Schwartz describes, ìPermaculture combined with deep ecology combined with cultural animations. That practice of breathing life into a place through the arts – through ritual.î

ìThe Greens synchronize all those different definitions ñ itís [the Green Party] broad-based, itís multicultural, it cuts across class lines, and it brings people together.î The scenes from the community projects Schwartz facilitates ìemerged from community but also emerged from history and crossed over in real life.î

Using the arts to transcend differences and transform places, Schwartz describes Green arts as a way ìto involve people in creative community ventures,î that can be outside our comfort zones, outsmart the recession, and foster local self-reliance.

ìA green mural is rich in process,î Schwartz notes. Green holistic trends emphasizing community participation from gardens to murals to cultural exchanges may very well lead us to a new industry of Green Arts Workers who will usher in the changes to come.

Ramona Moonflower Rubin ñ Standardization of medical marijuana

With an emphasis on public health, epidemiologist Ramona Moonflower Rubin from the San Francisco Bay area directs a scientific laboratory that analyzes medical marijuana. Ramona has a vision for creating public health safety standardization of the healing, therapeutic and recreational herb, which the White House continues to criminalize despite local and state dissenting policies.

With an emphasis on public health, epidemiologist Ramona Moonflower Rubin from the San Francisco Bay area directs a scientific laboratory that analyzes medical marijuana. Ramona has a vision for creating public health safety standardization of the healing, therapeutic and recreational herb, which the White House continues to criminalize despite local and state dissenting policies.

After nearly a century-long ban on cannabis in the United States, widespread usage and proven medical benefits affirm the need to lift the prohibition. ìThe current absence of regulation is an opportunity to create sound policy and practice and to acknowledge its proven medical value,î Rubin said.

Placing value on the Green Partyís presence in local, state, and national spheres to help in the debate to legalize marijuana, Rubin frowns on the non-functional two-party system in the United States. Rubin said the two party system limits dialogue. ìWe donít live in a world where we can define ourselves on two sides of a line. You donít get all sides when only two are represented.î

An advocate of non-profit canna-businesses, Rubin refers to collectives and cooperatives networking to raise and provide the compassionate medicine, as well as, the ìneed for regulation to ensure safe handling of medicine to patients.î Rubin is a cofounder of Doc Greenís Healing Collective that offers topical cannabis lotions called ìDoc Greenís Therapeutic Healing CrËmeî to relieve pain, inflammation and soreness.

Rubinís history as a public health expert favors local empowerment because, ìthe government is not always going to come up with the most efficient way to do things.î During time spent volunteering in Mississippi after Hurricane Katrina, Rubin participated in a consensus-run free medical clinic, which functioned as a community-meeting place with a kitchen, food, and access to medicine.

Storm Waters – Revolutionary change

Ecologist and accomplished storm chaser, Storm Waters also known as ìThe Radikal Weathermanî reflects in a collection of accounts of the World Trade Organization (WTO) protests of 1999 in Seattle http://realbattleinseattle.org/node/124. In his account he notes the culmination of decades of activism, and a new beginning in radical change. The Wyoming Green voter saw these events as his own political awakening.

But it didnít just start at the protests; Waters had been building on his political approach for all of his adult life. ìAs a Peace Corps volunteer in West Africa during the late ’80s, I learned directly from indigenous elders in the African bush that deforestation was disrupting local, regional, and global weather patterns, bringing about socioeconomic and geopolitical destabilization ñ and certain disaster, for people and animals alike. It was here also that I saw neoliberalism’s work first hand; teaching me the true meaning of poverty and disenfranchisement,î he said.

In the 1990ís, ìwhile shooting and editing documentaries in solidarity with indigenous peoples around the North American continent who were working on similar issues… I recognized the same patterns on this continent that I had seen in Africa: devastating land-use policies, ecocide, cultural genocide, neocolonialism, plantation economics, poverty, gentrification…î The indigenous from the Americas, ìreinforced my impressions regarding global justice, human impact on climate, and the interrelationship between them.î

Waters describes the WTO as the culmination of a decade of work. ìIssues were brought together and people’s overall understanding took a quantum transcendent leap,î at the WTO protests. ìThe people in the street agreed to speak to the cameras and recorders, and the whole world saw and heard ñ whether the establishment wanted this or not.î

ìIt really felt to me that revolution, if not accomplished, had just gone from the theoretical to the tangible. Ö I think what made this so subtly spectacular is that in the streets of Seattle, we pledged solidarity with the truly oppressed peoples of the world (which includes all other species) and in the succeeding months at Buffalo Field Campaign and Black Mesa (and elsewhere), and we put our effort where our rhetoric was. We continued learning ñ from the Natives, from the buffalo, from the wind and the sky and the trees and rivers and all the peoples. That’s a miracle unto itself…that’s revolution.î