Mixed results in German Federal Election

Share

by Phil Hill, B¸ndnis ë90/Die Gr¸nen

by Phil Hill, B¸ndnis ë90/Die Gr¸nen

It was the best result the Greens had ever had in a German national election ñ 10.7 percent ñ but nobody at the September 27th election-eve party was cheering as the first exit poll results were announced, for they came after the results of all the other four major parties, and there had been plenty of bad news there. First, Chancellor Angela Merkelís conservatives (CDU), though weakened, was clearly headed for victory, but this time without having to rely on the moderate-left Social Democrats (SPD) to form a government, as she has for the past four years. Among the three smaller parties, the Greens were once again the weakest ñ both the Left Party (the former East German communists) and the centrist-liberal FDP had scored bigger gains. And finally, the SPD, with whom the Greens governed in a Red-Green coalition from 1998 to 2005, suffered the worst election disaster in its 140-year history.

The only thing that got the Greens cheering that night at the old post office at Berlinís East Station were the rousing speeches by the former cabinet ministers who led the campaign, ex-Environmental Minister J¸rgen Trittin and ex-Consumer Affairs and Agriculture Minister Renate K¸hnast. Both promised a powerful opposition to the incoming coalition government, both inside and outside of parliament. The latter is particularly planned in case the governing parties try to implement their campaign promise to extend the life spans of nuclear power plants, limited to 32 years under a deal negotiated by Trittin with the nuclear industry when he was in office. Under that deal, two of Germany’s 19 nukes have already been shut down, and the last one is scheduled to close by 2020. Polls show that people are strongly in favor of keeping to that schedule and continuing to expand alternative energies, especially wind power, which is abundantly available in northern Germany. Plans for offshore windmills are already being realized, and such alternatives are so well established that even the new government wonít challenge them.

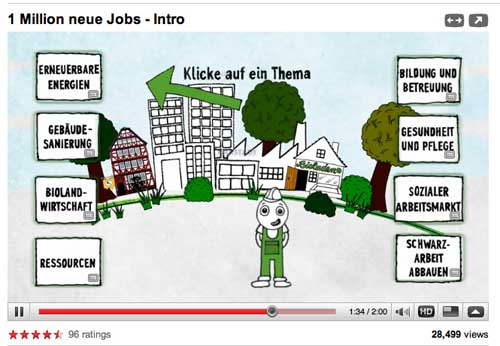

Trittin also attacked Germanyís ìcash for clunkersî plan, the worldís first, as ìdrinking to avoid a hangover.î ìNow that the party is overî ñ the fund ran dry this summer ñ the hangover is here in full force: dealerships are lonely places, since everyone who wanted a car has already bought it. In the meantime, Germanyís automakers are lagging behind in the development of electric cars and a Green-less government is unlikely to do much to change that. On the other hand, Germanyís fundamentally healthy ìreal economyî has been less badly affected by the economic melt-down that has devastated the US and some other countries. In Germany the Green jobs program created ten years ago during the Red-Green government is part of the reason why.

Trittin also attacked Germanyís ìcash for clunkersî plan, the worldís first, as ìdrinking to avoid a hangover.î ìNow that the party is overî ñ the fund ran dry this summer ñ the hangover is here in full force: dealerships are lonely places, since everyone who wanted a car has already bought it. In the meantime, Germanyís automakers are lagging behind in the development of electric cars and a Green-less government is unlikely to do much to change that. On the other hand, Germanyís fundamentally healthy ìreal economyî has been less badly affected by the economic melt-down that has devastated the US and some other countries. In Germany the Green jobs program created ten years ago during the Red-Green government is part of the reason why.

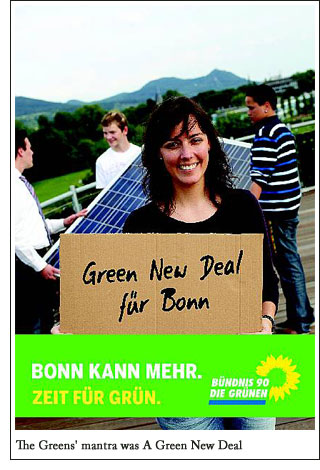

Of course, Green spin doctors tried to accentuate their gains, and for good reason: Unlike the other smaller parties, the Greens seem to have ìput on muscle,î rather than fat, having seen real growth in their core support, especially among young people. Their election platform of a Green New Deal to revitalize the economy through investment in Green production, particularly in the energy area, gave the Greens a clear and unique identity; on the other hand, they had no realistic option for governing, which cost them support, since those who wanted to back a winner voted for the old parties, and those who just wanted to protest could always vote for the Left Party, which refuses to consider joining a federal government.

By contrast, the gains of the other two smaller partiesí involved mostly voters who will probably retain their long-term loyalty to the big parties. On the other hand, there were a number of small protest parties whose very good results reflect dissatisfaction with the way the Greens are doing their job as representatives of grass-roots movements. The most significant was the ìPirate Party,î a grouping of mostly young people concerned about government snooping and censorship of the Internet; its Swedish sister party won a seat in last summerís European election. Significantly, that legislator is now a member of the Green Caucus (Greens/European Free Alliance) in the European Parliament in Brussels. Counting the votes of this and other small ìgreen-leaningî parties ñ all of which failed to reach the 5 percent threshold, and are thus ignored in allocating seats ñ the ìoppositionî actually got a few more votes than Merkelís coalition. Thus, the Greens have their work cut out for them, to reestablish their base in the movements.

By contrast, the gains of the other two smaller partiesí involved mostly voters who will probably retain their long-term loyalty to the big parties. On the other hand, there were a number of small protest parties whose very good results reflect dissatisfaction with the way the Greens are doing their job as representatives of grass-roots movements. The most significant was the ìPirate Party,î a grouping of mostly young people concerned about government snooping and censorship of the Internet; its Swedish sister party won a seat in last summerís European election. Significantly, that legislator is now a member of the Green Caucus (Greens/European Free Alliance) in the European Parliament in Brussels. Counting the votes of this and other small ìgreen-leaningî parties ñ all of which failed to reach the 5 percent threshold, and are thus ignored in allocating seats ñ the ìoppositionî actually got a few more votes than Merkelís coalition. Thus, the Greens have their work cut out for them, to reestablish their base in the movements.

In broad terms this election is historic, since it fundamentally overturned the old party system in which the CDU and the SPD were the ìmass partiesî that ran the country, virtually always getting between 35 and 50 percent of the vote, while the Greens and FDP were their potential junior partners, and rarely cracked the 10 percent barrier; after reunification, the old communist party, the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS), too, was in this category. This time suddenly, all five parties are within the previous ìempty rangeî of 10 to 35 percent, largely because the SPD lost so dramatically, with over a million voters switching to the Left Party (as the PDS is now called, after merging with SPD dissidents) and two million voters staying home. If Merkelís deeply divided party also splits, as the SPD has in effect done, the country could end up with six parties, which might all score between 15 and 25 percent of the vote.

In the last federal election the SPD lost considerably after a leftist faction within the party split-off and broke away in disgust with SPD Chancellor Gerhard Schrˆder. In 1998, Schrˆder was elected with twenty million votes; this time, only ten million were left, or only 23 percent. Thatís a level the party first attained in 1893, and to which it dropped back again only during the crises following World War I and just before the Nazis came to power. This illustrates the dimensions of its present catastrophe. The primary reason was Schrˆderís drastic cut-backs in social programs during his administration ñ particularly in unemployment and health care. Designed to deal with the nationís budget crisis, many measures were necessary and some were even improvements ñ such as making health insurance mandatory for all, at no cost if necessary. But there were also significant mistakes that were considered brutally unfair to poor and working people. The Greens are calling for significant corrections to these, and the SPD, now seems to be moving in the same direction. The partyís new chair, G¸nther Gabriel, the environmental minister under Merkel, kept up a fairly consistent battle to maintain the anti-nuclear policies implemented by the SPD-Green government.

State-level elections were also held in five states and the results were a mixed bag for the Greens, who had hoped to end up in the government in all five, and had to settle for only one, in the Saarland. However, only in the East German state of Saxony, did Merkelís alliance win an outright victory. In Schleswig-Holstein on the Danish border, it seems to have won a narrow margin in the legislature in spite of an electoral majority for the splintered left-of-center parties, due to a weighted counting system there. In Brandenburg, which surrounds Berlin, the SPD retained power, and can now decide whether to rule with the support of the CDU or the Left. Unfortunately the condition stated by SPD Premier Matthias Platzeck (a former Green state environmental minister in the early 1990s!) was that the state had to continue to support the disastrous strip-mining program in the region of Lusatia. The Greens did, however, re-enter the Legislature there, and a neo-Nazi party was booted out by the voters. In Thuringia, another East German state, the Greens were back in the legislature, and had hopes for a three-way governing coalition with the SPD and the Left. But at the last moment, the SPD decided to join a CDU-led government instead.

In the fifth state, the Saarland, which borders Luxemburg, the SPD and Left won the same number of seats as the CDU and FDP together, so the Greens got to decide to whom they will give their support. While many Greens there seemed to prefer a deal with the ìreds,î a major problem is that the main issue in the state is coal mining ñ which those parties support, in deference to the minersí union. By contrast, the Liberals and Conservatives ñ and the Greens ñ are backing a citizensí movement that wants to close down the industry because the mines run under urban areas and are causing damage to houses. The Left Party caucus also includes some legislators with ties to a shady, and some say criminal, character who was previously expelled from the Greens.

Ultimately the Greens decided upon a coalition with the Liberals and Conservatives. The Greens were wooed so ardently by both camps that they were able to† realize most of their demands in the key areas of environmental policy,† education and rights for immigrants. What tipped the balance was the announcement by Left Party national chair Oskar Lafontaine that he would† return to the Saarland the head his party’s legislative caucus. Green state chair Hubert Ulrich feared that the erratic and virulently anti-Green former Social Democrat would dominate the state government.

Green national campaign manager Steffi Lemke in front of a party campaign poster saying "climatic protection works"

Some Greens feared that combined with the SPDís switch to join with the CDU in Thuringia, this decision in favor of the center-right would not send a very strong message to those who hope to be able to recover from this election and retire the Merkel coalition in four years. But Greens at the national level were quick to assure their supporters that this surprising turn of events in Germany’s second smallest state is not a harbinger of things to come elsewhere. ìI’m a very imaginative person,î Green Party national manager Steffi Lemke told the Berlin Tageszeitung in an interview on October 23. ìBut even my imagination is insufficient to foresee such a coalition at the national level.î That position was certainly reinforced that same day as the Conservatives and Liberals at the national level unveiled a healthcare reform that shifts the burden of paying for healthcare disproportionately to poor and working people. All three opposition parties at the national level were equally outraged.

The first step in unseating the new CDU-FPD coalition will be the elections in North Rhine-Westphalia in the summer of 2010 ñ the state that is home to almost a quarter of Germanyís people and where the Greens hope to build upon the 6.4 percent of the vote they received in the 2005 election.

Phil Hill is a former Green organizer from the United States who now makes his home in Germany and is active with B¸ndnis 90/Die Gr¸nen. He has previously written about the German Greens for Green Pages.

Report from the Berlin Congress (July 2009)

www.gp.org/greenpages-blog/?p=1252

Do elections spell the end of Germany’s “Green era?” (October 2005)

www.gp.org/greenpages/content/volume9/issue3/world3.php

For more information about B¸ndnis ë90/Die Gr¸nen: www.gruene.de/